READING IS POLITICAL, WORDS ARE PROTEST

During the 1960s, Walter Rodney exploded Jamaica and the Caribbean with a fire to protest this colonial hell that we’ve perpetuated through silence. When grounding with his brothers, who are my brothers too, he professed with clarity that government men “are afraid of that tremendous historical experience of the degradation of the black man being brought to the fore.”[i]

Rodney’s speeches dropped like bombs in the outside spaces of the University of the West Indies, Mona Campus. And while students scrambled to collect his words and re-cast them as a wake-up call of shrapnel across Jamaica’s capital city, the University’s administrators of peace sheepishly sought shelter and the government went about banning all Black uprising. In October 1968, the third Prime Minister of Jamaica, Hugh Lawson Shearer, successfully banned Dr. Walter Rodney from re-entering Jamaica. Also denied entry were Stokely Carmichael and James Foreman. Similarly, the ports and wharves would not let in the published words of Carmichael, Malcolm X, and Elijah Mohammed. But Rodney’s words had already awakened the consciousness of Black people, from the Black intellectual to the Black masses, and so they protested his ban on foot and with fire. Yes, Rodney had started a fire that burned threateningly for a time. And though he tried to keep those embers lit, tragically on June 13, 1980, Walter Rodney was exploded by the planted bomb of an assassin in the capital city of Guyana, his home country. His body, like his message, cast in a million black directions.

As I reflect on race and racism the Caribbean, as I think about the politics of hate in the Caribbean, and as I question decolonial thinking in this region, I cannot help but think of Rodney. The protests in the United States demand that the American government, the nation’s businesses, and the country’s citizens must do better. They must acknowledge the full humanity of Black people. But what we seem to forget here is that the fight of Black people in one land is also the fight of Black people across the diaspora. Black Americans and Black Caribbean people face discrimination and prejudice today that was born from a colonial past that was not as long ago as we like to pretend it was. As Dave Chappelle reminded viewers in his very recent “8:46” Netflix special, slavery was the experience of our grandparents’ grandparents. Add to that, that colonial independence was only granted recently, and that some readers of these words were born in European colonies. Rodney knew this reality. Yesteryear and today are more alike than not.

I carried Walter Rodney with me last October when I journeyed to Georgetown, Guyana. My purpose in Guyana was to deliver an academic presentation that explored the role of the Caribbean writer to encourage not just an empathetic reaction in readers, but the role of the Caribbean writer to provoke political action. I was thinking, in particular, about how raced words tend to stick with all of us, especially writers, forcing us to roll those words around in our heads, questioning their roots and their intentions to divide and destroy. As a Black girl and a Black woman in America, I heard so much prejudice, sometimes veiled and sometimes not. (I will never forget when a white high school mate ceased being my friend in the simple utterance of blind words to me: “Isis, you got into UPenn because you have the Black thing and the woman thing going for you.”) And as a brown girl and somehow a one-time “white” woman in Jamaica, I realize that I can deny but cannot escape Jamaica’s categories of prejudgment. (I learned last year that a UWI student once described me as “the white version” of an unnamed Black woman lecturer in another department.) Yes, raced words stick with us as we try to make sense of their roots and intentions.

During my time in Guyana I tried to see what Rodney may have seen. I wondered what he had experienced in Guyana that could make him write and feel what he wrote and felt about Jamaica and the Caribbean overall. I attended a dramatic performance by the National Drama Company called Laugh of the Marble Queen, a performance that sucked the oxygen out of the theater. The playwright Subraj Singh, explained after the gruesome show that his play was meant to highlight the legacy of colonial problems in Guyana. He felt that a realistic play would force a dialogue about the atrocities that take place every day and are no different from those that took place hundreds of years before. His play was nothing like the Jamaican reaction to horror of tek bad sinting mek joke. With on-stage rape and on-stage police brutality happening just twenty feet from one’s eyes, there was no possibility of laughing through the discomfort. This performance portrayed the violence done to Black bodies in jaw-dropping detail. So vivid was the work that Mr. Singh noted that the originally cast “evil white Marble Queen” had quit the play after her first performance because a mob of Black and Indian audience members were so unwilling or unable to see a line of distinction between the fictional evil white woman character and the white woman acting in the role, that they gathered together, followed her, and threatened her life. The play’s actors and writer took no responsibility for the post-performance violence; rather, they saw it as evidence of the racial strife that is always just below the surface. Recalling that evening, I can still hear the shrill scream of the woman acting out being raped by a white overseer/ police officer. In that moment, I felt the strong memory of Rodney who used words to stir people out of the slumber of oppression so that there might be no more cause for scenes like these to unfold on the streets or on stages.

When I was leaving Guyana, airport security flagged my backpack for inspection. The agent asked what was in my bag. I responded, “books and two laptops.” Travelling on my Jamaican passport with Walter Rodney, Wilson Harris, Jan Carew, Pauline Melville, and Grace Nichols in my luggage and in my computer files, I realized I was carrying intellectual contraband. I looked the agent in the eye. When my backpack went through the scanner the contents were clearly outlined, but the titles were not. He looked at me as he adjusted his latex gloves and extended a prodding wand. I cocked my head and clenched my jaw, daring him. He unzipped my bag, rummaged through the books and extracted the thinnest of the texts, Rodney’s 1969 publication of Grounding with My Brothers. He saw that pages were dog-eared and other pages had pink sticky notes attached. I cocked my head the other way. “What business did you have in Guyana?” he asked. I recalled my few days at the conference, the triggering theater performance, and an unplanned visit to CARICOM to discuss the role of literature in Caribbean education. “I was here for academic purposes; literature.” His brow wrinkled, seemingly disappointed. I suppose my response struck him as non-threatening. He fanned the pages, closed the book, and placed it back in my bag. As he zipped it shut, he said “I hope you enjoyed your stay.” “Yes, I learned a lot.” But even as I would board the flight out of Guyana, there was still much more to learn.

As a Black girl and a Black woman in America, I heard so much prejudice, sometimes veiled and sometimes not. (I will never forget when a white high school mate ceased being my friend in the simple utterance of blind words to me: “Isis, you got into UPenn because you have the Black thing and the woman thing going for you.”) And as a brown girl and somehow a one-time “white” woman in Jamaica, I realize that I can deny but cannot escape Jamaica’s categories of prejudgment. (I learned last year that a UWI student once described me as “the white version” of an unnamed Black woman lecturer in another department.) Yes, raced words stick with us as we try to make sense of their roots and intentions.

My long-time friend, Dr. Anita Baksh, had been with me during the conference and she stayed in Georgetown for a few extra days to carry out some research of her own. She is Indo-Guyanese herself and spent her early childhood in the country. While I was bouncing from island to island via a very indirect Caribbean Airlines itinerary back to Jamaica, Anita had visited Guyana’s national library. When she finished gathering what she needed, the library staff advised her to wait for a taxi inside for safety reasons, but as the time drew near for the taxi to arrive, she made her way to the sidewalk. Outside on the street she stood. She saw an older Black man coming her way and as he saw her, he began cursing. He then took a wide arc around her and sputtered, “I not passing by no fucking coolie.” She looked around. She was scared. There were two other women outside waiting for a taxi. They were Black. Anita told me that they just looked back at her with wide eyes. She saw a Black man outside talking to a security guard and he said he’s sorry for what that man said to her. But no one said anything to the cursing man who disappeared down the street. She willed the taxi to come sooner. When my friend shared her experience with me, I cried. I hurt for my friend. I hurt for her even though she is from another country and her foremothers are from another continent than mine. I hurt because I recognized that her humanity was threatened simply because this system of oppression in the Caribbean subjugates all who are non-white and conditions its subjects to enact hate upon each other.

In the case of the contemporary Caribbean, prejudiced readings of bodies have led to oppressive systems, oppressive laws, and complicit citizens who can only offer a wide eye or an empty sorry when that which is usually below the surface erupts. But when wicked words are hawked and spit out on sidewalks in Georgetown, we should all be disgusted, all across the Caribbean. We should be disgusted because colonial fears led the British to pit Black against Indian, Indian against Black, and all against the indigenous in Guyana. We should be disgusted because systemic race-based inequality has made violent eruptions possible and shamefully common.

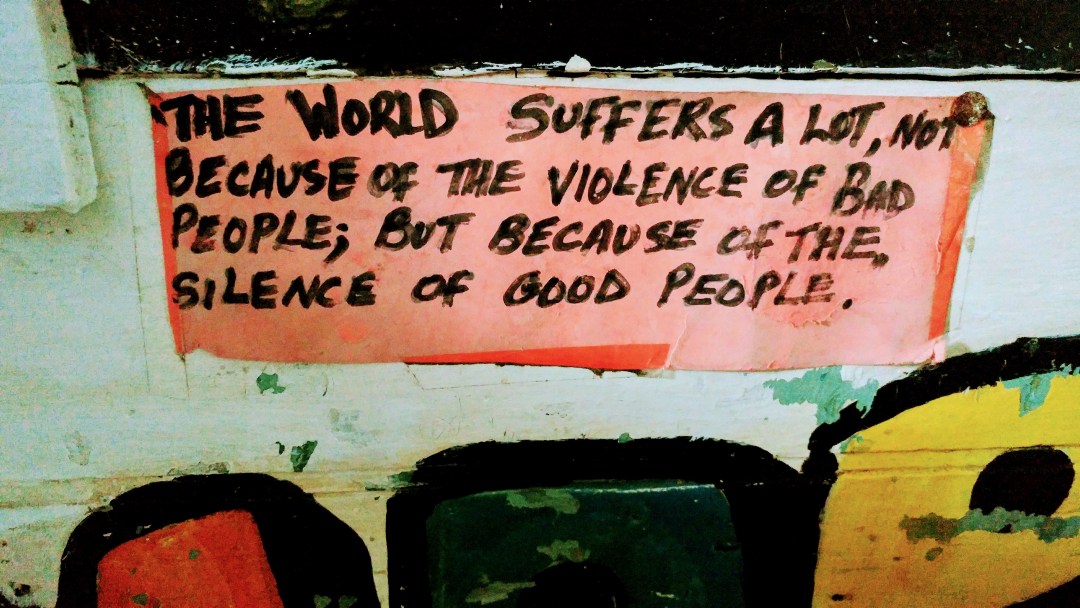

I have visited friends across the Caribbean and I have grounded with brothers and sisters in the land of Walter Rodney’s birth (and death). And I teach at the very campus that fifty years ago saw riots in reaction to the Jamaican government’s declaration that Rodney was a persona non grata. The frustration is the same and the excuse is the same from then and there to now and here. Many of us say nothing will change because we no longer have a culture of en masse protest, but that is not true. Scan Caribbean Twitter and Caribbean newspaper op-eds and we will see hundreds and thousands of avatars lending digital support to local and regional protests. In the hashtag and the Whatsapp circulated petitions shared across the class distinctions, we find a virtual voice of protest.

We must continue to read and re-read Caribbean poets, writers, thinkers, historians and there we will see that the protest has always been in the word. We never stopped protesting. We just stopped recognizing the power of our own words. It’s time now to re-ignite our activism by bringing our words together with purposeful intent to challenge this system of complacency that guarantees our oppression. It’s time we speak and write and raise our voices in protest against the only system that we have ever known. In a region that walks daily with historical trauma, a region where we exist in a complicated relationship with basic survival, I know that to intentionally shatter one’s only known reality through confrontation or protest will take a psychological strength that we have been conditioned against for hundreds of years. If we don’t though, we repeat this history forever.

[i] The Grounding with My Brothers. Walter Rodney. (1969: 62).

Poster of Walter Rodney in anchor image is the work of the late creative activist Michael Thompson aka Freestylee. Other images are by Isis Semaj-Hall.

Isis Semaj-Hall is the Riddim Writer, a co-founder and co-editor of PREE. She blogs pon di riddim, podcasts For Posterity, and lectures in Caribbean literature and popular culture at UWI, Mona. She is a decolonial feminist and cultural analyst with a creative practice that is nurtured by sound, emergence, and the digital.

Always something more to learn from these stories. Racism, has no boundaries, it promotes hatred amount the colored people.